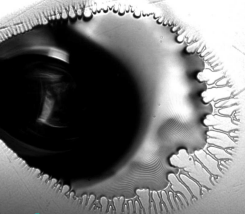

On January 2020, my collaborator Dr Victor Kang saw a geometrically appealing observation, while performing receding-contact-line tests on pitcher fluids (as part of our previous collaboration; see the article here). What he observed was the formation of fractal-like ordered structures when the drop of a pitcher fluid is withdrawn inwards. These structures were formed at the periphery of the drop.

We accidentally met at the Churchill college dining hall when he explained me the observation (showed the videos later). It immediately captured my attention, I think, because of two reasons: first, was the Platonism (perfect mathematical structures) these biological substances in nature exhibited (although with human intervention of performing experiments, i.e., finding right combination of forces and interactions – involving a bit of serendipity – which led to this observation); and second, was my irrational belief that maybe it has got something to do with singularities. Not to mention that I spent almost two years, since of the start of my Ph.D. in 2018, reading plenty of articles on contact line singularity, black hole singularity, pinching-off-of-drop singularity, and plenty more (the wonderful book by Jens Eggers and Marco Fontelos is also a delightful and rigorous read; despite some condoned issues of surface forces in the thin-film equation).

Singularity in a physical system is a vast topic that deserves a separate article devoted to it. For some weird reason, I was always drawn to this topic, the fact that the physical quantities reach infinity when they become singular, and if that is true, then it is weird, because what is infinity after all for a physical quantity. Surely, the mathematical world needs to be faulty enough to cause/create such singularities.

Nevertheless, Victor and I performed few more experiments and designed some setups to investigate the phenomenon further. However, pandemic hit and Victor had to wrap up his Ph.D. Somehow, the project stalled and I suggested my supervisor, Ian, to let me work on its theoretical treatment. I thought of using hyperboloidal coordinate systems to write the Navier-Stokes equations and see if the get these filaments (which we saw as hyperboloids in our AFM-FTIR investigations). However, Ian suggested me to build an experimental setup by myself in the lab and replicate this observation with non-biological fluids. I was drawn to this idea, because, in this way, I could do an experiment on non-biological systems and later on, work on the theory, to compare the results against (without worrying about the variability that biological systems often entail if I had used pitcher fluids as model systems).

In next one year, during pandemic, when the labs were on or off some times, I tried several experimental systems and finally chose one, that of a glass slide hanging vertically from a clamp, at variable angles, that allowed me to comfortably see the formation of filaments. Varieties of fluids – Newtonian and non-Newtonian – were tested and the angle of inclination of glass slide w.r.t gravity was varied.

After getting experimental data, we found that there was a clear separation between parametric regime where the filaments were formed versus where the filaments were not formed. In particular, the fluids with very small thin-film height yielded filaments, however, the thick-film with larger thin-film height did not yield such filaments. This, to me, looked very appealing to write a physical theory. However, I had no clue where to begin with.

The literature on contact line motion and evolution is vast and replete with analysis of contact line singularities and contact angle evolution as the contact line moves. I initially thought that the filaments were formed because of Plateau-Rayleigh instability as reported before in the literature. However, the experiments didn’t suggest that (which is why I am happy that I performed experiments first and didn’t immediately jump to building a theory – which is what I enjoy but probably was not something to do here). The experiments suggested that the filaments formed immediately as soon as the thin-film touched the substrate. It is just that the motion of contact line made it apparent as to what is the spacing between the filaments etc.). I was convinced that it is something fundamental – inherent in the thin-film itself – that yields such filaments. The motion, nature of fluid, type of setup are just parameters of convenience that makes it convenient for us to observe and analyse filaments. I did a literature search again and found that the thin-film equation, if evolved with time, for certain parametric conditions, yield physical singularities which look like a cusp-form and as the thin-film approach the singularity, it breaks into two entities. It immediately struck to me that this is what the experiments suggest and there is no way this can not be an explanation for what I have observed. I was cautious all throughout this thought-process though, as it’s easy to be drawn by a wrong idea and waste couple of months on the way.

After working through the theory, with help from some friends and attending a summer school, I did convince myself that the singularity yielded in the thin-film equation evolution with time has a direct correspondence with the filaments observed in the experiments. A couple more experiments and comparing against the theory made that belief stronger.

The preprint is now out and available here.

There could be many take-aways here. And I am not yet a retired scientist to give suggestions or opinions. However, what’s exciting road ahead for me is to prove that such hydrodynamic singularities that the nonlinear equations in fluids (be it thin-film equation or the monster Navier-Stokes equations) do exist in mathematical reality. That is to say that, for an arbitrary initial smooth Cauchy datum to Navier-Stokes equations, in a finite-time, the velocities, vorticities, and pressure field approach infinity in a smooth way. When I say smooth, I mean, infinitely-differentiable.